Ebo, Sister Mary Antona

Sister Mary Antona Ebo was a well-behaved woman who DID make history as one of the Sisters of Selma who marched for voting rights for African Americans in 1965.

She was born Elizabeth Louise Ebo in 1924, one of three children born to Daniel and Louise Ebo. She was known as “Betty Lou” wen she was younger. In 1930, after her mother died suddenly, and her father lost his job during the Great Depression and could no longer care for the children, Betty and her two siblings became wards of the county and were placed at the McLean County Home for Colored Children. She lived there off and on until 1942.

Though raised Baptist, Ebo was drawn to Catholicism during two extended hospital stays in her adolescent years. She soon was received into the Catholic Church. However, because of her conversion, she was barred from returning to the Home for Colored Children by its board of directors. Arrangements were made for her to attend Holy Trinity High School so she could complete her education. Betty graduated in 1944—the school’s first Black student and graduate.

After graduation, Betty applied to Bloomington’s St. Joseph’s School of Nursing, but was denied entrance because of the color of her skin. Other schools also refused her admission because she was Black. Finally, she was accepted by a new school, St. Mary’s Infirmary School of Nursing for Negroes in St. Louis. This was the nation’s first and only black Catholic nursing school at the time. Two years later, the Sisters of St. Mary’s decided they would accept Black novices. Betty became one of their first Black nuns, taking the name Sister Mary Antona in honor of the nun who taught her algebra and geometry at Holy Trinity. She took her first vows in 1947 and served with the Franciscan Sisters of Mary for 71 years.

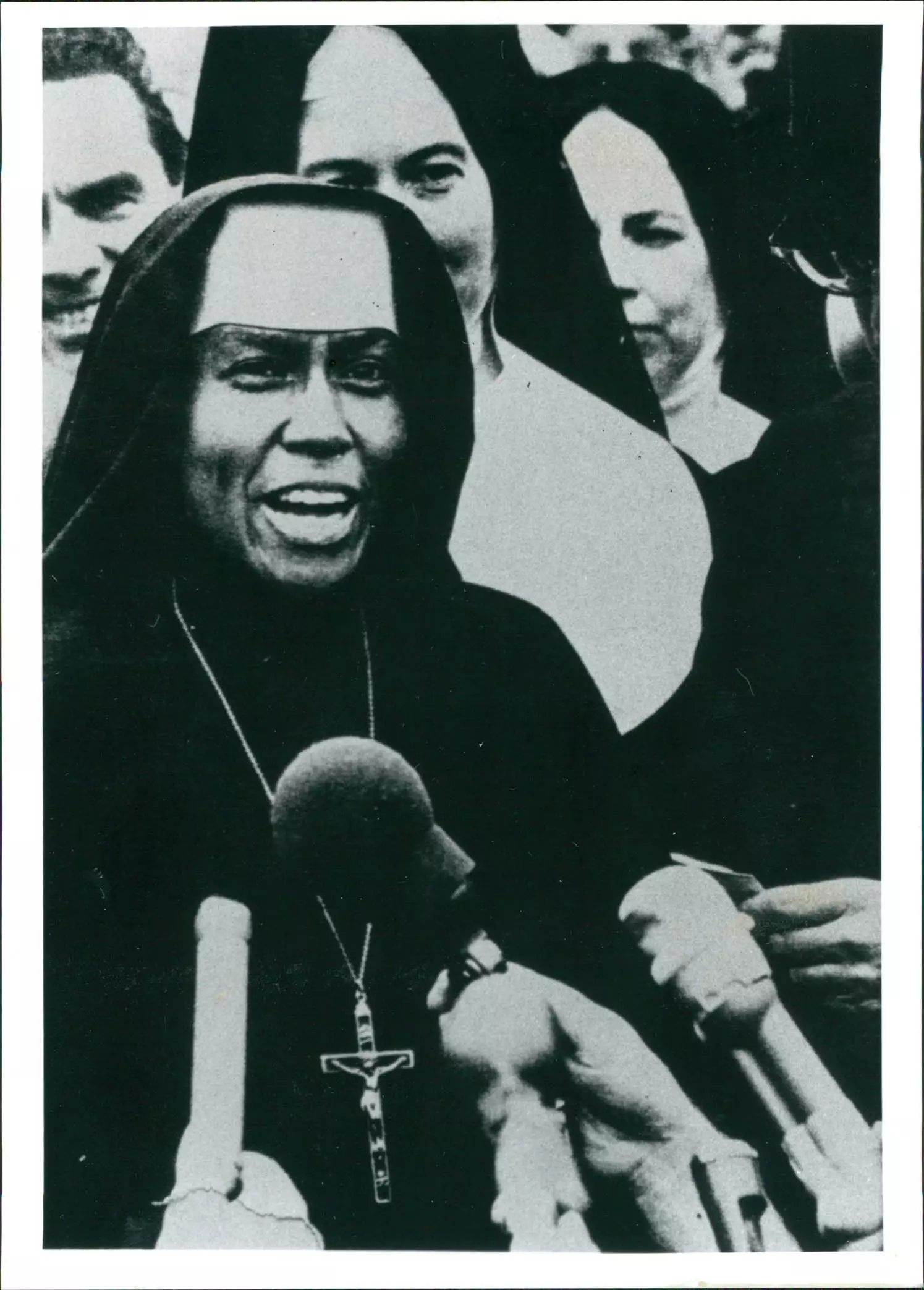

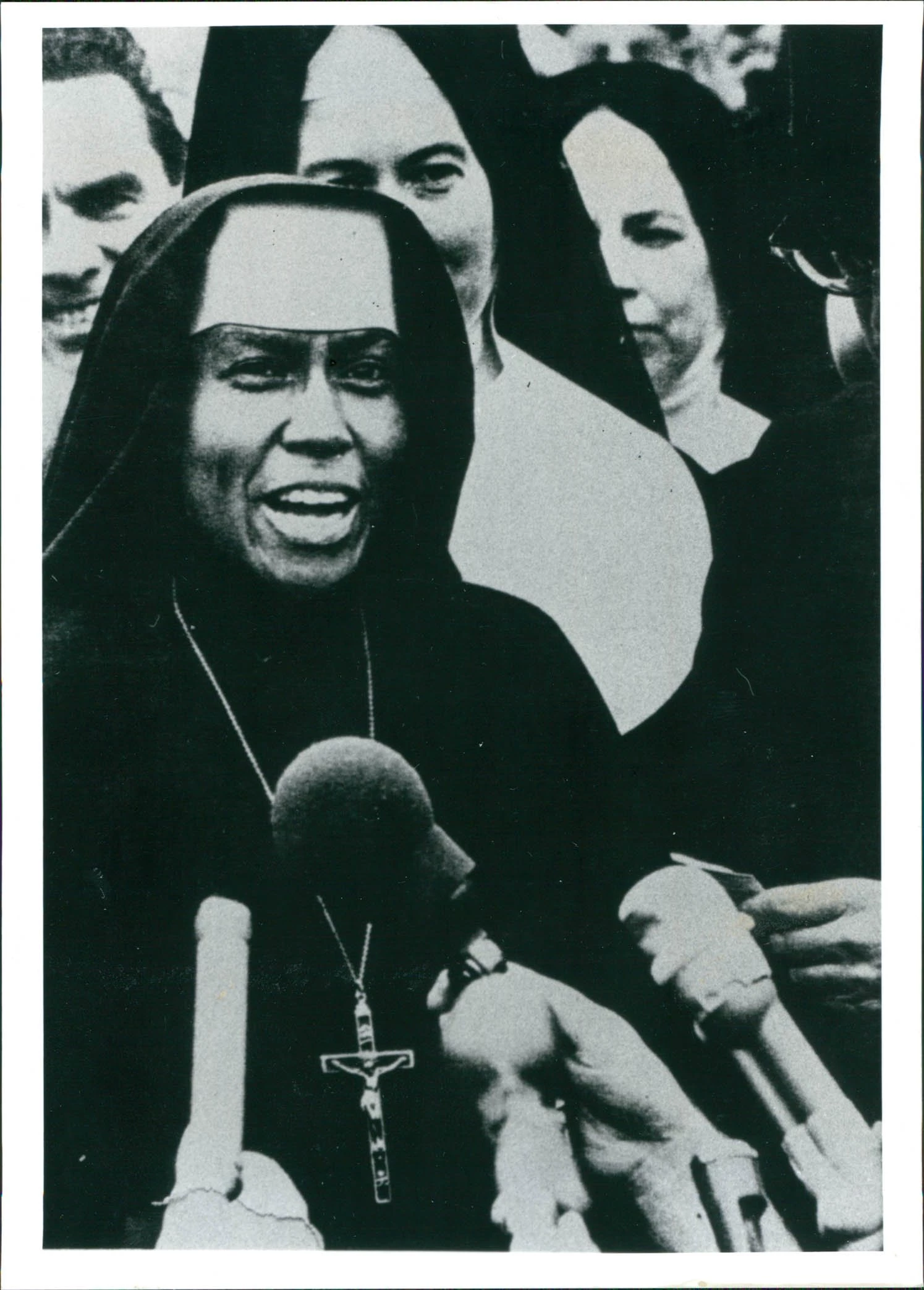

While she was working as Director of Medical Records at St. Mary’s Infirmary in 1965, she learned about “Bloody Sunday,” the voters’ rights march led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on March 7, 1965 in Selma, Alabama that turned violent when white supremacists violently attacked the peaceful marchers. She joined an interfaith contingent from St. Louis that answered Dr. King’s call for religious leaders to come to Selma. Her group arrived on the morning of March 10, 1965. Terrified but determined, she was at the front of the group of demonstrators that day. They were stopped by city officials just one block into the march. When reporters began asking questions, Sister Antona was pushed by her fellow marchers to respond. She did so with strength of character, stating “I am a Negro and very proud. I feel it a privilege to be here today…I might say that yesterday, being a Negro, I voted. And I’d like to come here today and say that every citizen—Negro as well as white—should be given the right to vote. That’s why Im here today.” Her story was shared in the 2006 PBS documentary, Sisters of Selma: Bearing Witness for Change.

At the age of 41, Sister Antona had found her second calling as a spokesperson in the Civil Rights movement. In 1968 she helped found the National Black Sisters’ Conference, whose members committed themselves to “moral fortitude” to confront racism on a daily basis “where you are at the moment.” In 1989 the organization recognized her contributions and awarded Sister Antona the Harriet Tubman Award for leadership and described her as being “called to be a Moses to the people.” She remained vocal about voting rights of not only African Americans, but all Americans. She has also been vocal about present-day racism and injustice that is seen in substandard educational opportunities for minorities and recent shootings of unarmed black youth until her death in 2017.